Willie Mays, working as a greeter for Bally’s casino at the time, pulled up to a rickety baseball stadium in a limousine that already had missed five turns on its way from Atlantic City to Bridgeton.

Google Maps? The Waze app? Forget it. Not for Mays — or his driver — and certainly not in the early 1980s.

Once Mays finally arrived, organizers from the Bridgeton Invitational Baseball Tournament quickly escorted their guest to the celebrity room — the second floor of an aging press box — where the only thing that resembled anything of a green room was the grass surrounding the field below.

Sentimentality could not calm Mays. Neither could the reminders of the other legends — Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, and Monte Irvin — who had visited the charming field before him.

Like the others, Mays' appearance was no gimmick, either. Dating back to 1967, the Bridgeton Invitational has been one of New Jersey’s iconic semi-pro tournaments and not just because of its famous faces in the crowd. It’s a tournament steeped in tradition — known for its speed-up rules — and stories like what happened next with Mays only have added to the intrigue of this South Jersey staple.

Mays was banned from baseball at the time for his association with the gaming industry, but the passionate local fans, a fence with chipped paint and old wooden bleachers resonated with Mays.

So as the story goes: Bob Rose, one of the tournament's organizers, waited for Mays at the bottom of the stairs with a local farmer who presented the Alabama native with a basket of peaches. Peachy keen? Not so much, according to Rose.

"Basically, he said: ‘Why would you give a guy from the South peaches?’" Rose told NJ Advance Media. “Instead of peaches, Mays wanted plums. No kidding.”

In exchange, Mays said he would donate one of his 12 Gold Glove awards to the museum across the street for a box of plums being grown down the road.

“Literally, he just said that,” Rose said. “So he comes out on the baseball field and tells the crowd. Back then, when he saw an old baseball field, it brought out some emotions. He was practically in tears seeing the old wooden bleachers. He tells the crowd: ‘I just want you to know I’m going to give you a Gold Glove for a box of plums.’”

<Mfailed> who died in June at 93 , he kept his word.

Rose picked up the Gold Glove from Bally’s within a week. The next year of the tournament, Mays returned for the enshrinement of his trophy and was presented with his long-awaited plums.

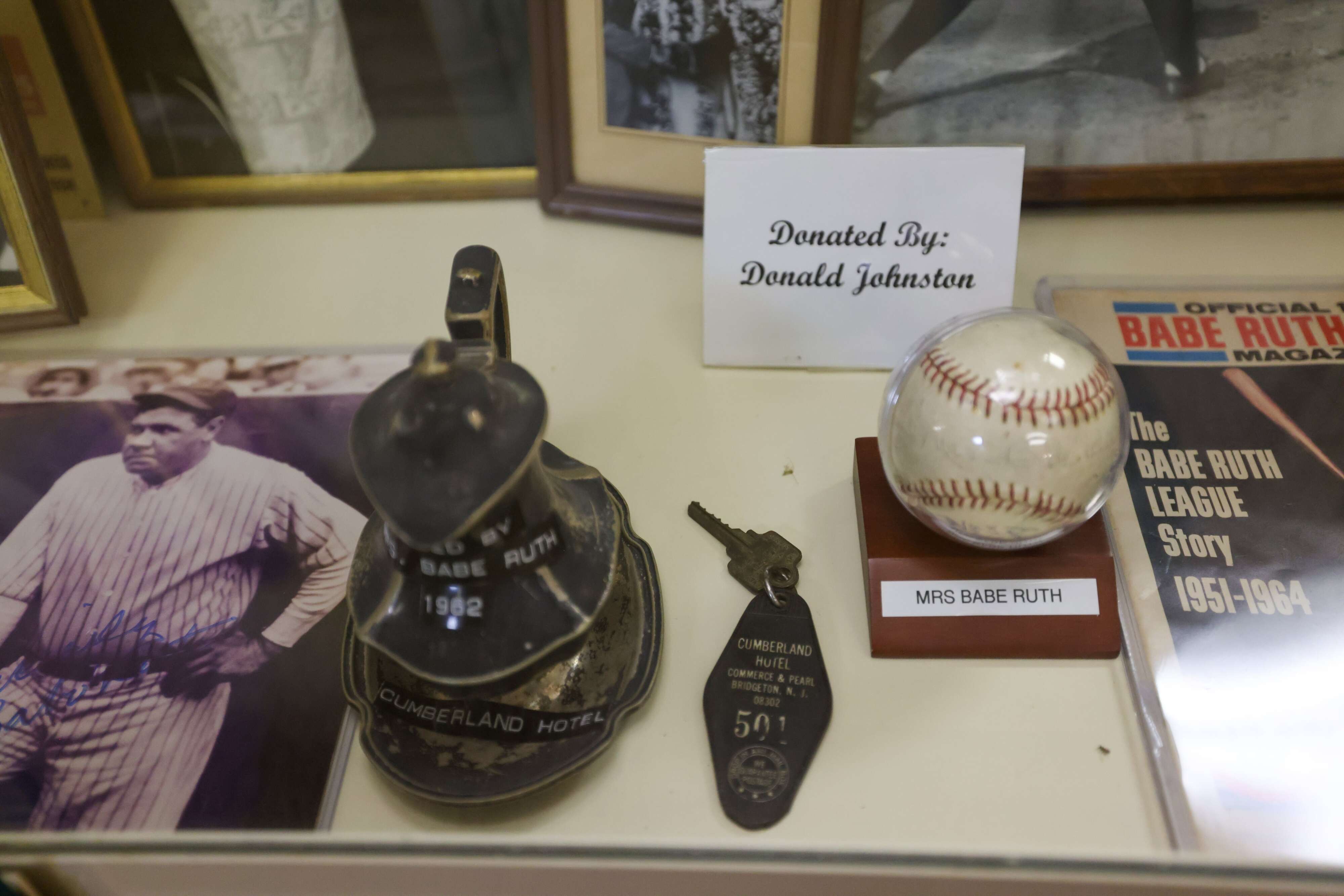

Since then, the Gold Glove, which was awarded to Mays in 1960, and a cream-colored “Say Hey” sweater that Mays pulled off his back that day have been housed at the All Sports Museum of Southern New Jersey .

The museum sits in a nondescript white ranch-style building that looks more like a field house fit for a grounds crew than the home of rare collections. Adding to its hidden mystery, the location has two addresses: 8 Burt St. and 8 Richie Kates Sr. Way, named after a local boxing star who contributed to the museum’s longevity.

The best way to find the museum is to locate Alden Field — the place where this story began. The white-hutted museum sits across the field and just adjacent to the towering bleachers of Bridgeton High School's football stadium.

The original museum was built by volunteer tradesmen in the mid-1960s and has since grown into a state-sponsored source of tourism. A donation by local educators, Carl and Peg Gray, plus support from the New Jersey Legislature helped expand the museum’s mission, which first served as Bridgeton’s Hall of Fame and eventually expanded to include memorabilia from the baseball tournament across the street.

Now, a dedicated group of retirees keeps history preserved within its walls. They don’t do it for money. They do it as a hobby. They rely on sponsorships, donations, and whatever funding trickles down from New Jersey’s tourism board. The visitors who pass through its doors do so for free and are left with the lasting impression that the side-door entrance and unassuming building they entered seems to go on and on with one room after another.

At a time when sports history continues to be lost, the executive directors of the museum hope to bring their hidden gem into plain sight.

Elsewhere, the Sports Hall of Fame of New Jersey, which opened in 1988, sits in the shuttered arena in the Meadowlands in East Rutherford. County hall of fames rely on volunteers to keep their missions going. Those can be hit or miss: Several — like the one in the Meadowlands — have faded into history.

But here, Dom Valella, Kevin Danna, and Ed Forman are dedicated volunteers preserving South Jersey’s history. Forman has served as the museum’s curator for more than 20 years.

Valella managed an Acme grocery store for 45 years. In his retirement, he works as an usher for Phillies games at Citizens Bank Park and also spends hours diving into binders of old newspaper clippings that have been stashed on shelves in the trophy room of the museum.

People like to say we’re a hidden gem," Valella said. "We’re the extension of the people who have come here.

At a time when newspapers continue to shrink, Valella has roughly 50 binders stuffed with clippings. He finds himself reading on most days as time zips by.

“There’s so much information here,” Valella said. “The people who certainly came before us at the museum did such a great job collecting these clippings. Admittedly, we need to chronicle these more.”

That’s the spirit that continues to push Valella and his team. What’s on display inside the museum makes up about one-third of its entire collection. The rest remains in storage. Again, nothing gets turned down.

The museum houses everything from Mays’ Gold Glove to the original Phillie Phanatic’s massive fuzzy shoes. It has a personal collection from Hall of Famer Leon “Goose” Goslin, who grew up in nearby Salem. There’s also a dedicated wing honoring athletes from New Jersey’s eight southern-most counties.

There are oddities like a French foil donated by a fencing coach from a local community college and an early pole vault pole used by Olympian Don Bragg , a native of Penns Grove. There’s an entire room filled with trophies, including one from a tug-of-war contest in 1904 — the oldest piece of memorabilia in the museum.

In one room, there are rows and rows of trophies stacked along tiers of shelves.

It seems like every story about the museum starts with a wrong turn. Just like Mays, Todd Frazier got lost on his way to Bridgeton, too.

Frazier, the New Jersey baseball-lifer from Toms River, was attending his induction ceremony when he got stopped by police — twice.

The former MLB All-Star, Rutgers standout and famed Little Leaguer was stopped for an illegal turn. He was lost — again — when police stopped him for the second time. When Frazier said he was that Todd Frazier, the officer gave him an escort to the white museum across town.

"The drive home was much better. I can tell you that," Frazier said.

As for the museum itself, Frazier has a fond memory, sharing his induction — and criss-crossed arrival — with his father.

It was special," Frazier said. "The stuff they have in there, I never would have imagined. It has this old-school feel, but it’s a really nice place. It’s worthwhile.

From the outside, you might miss the unsuspecting museum. The white cottage has a green sign for visitors.

It is all discreet. The sign. The building. The parking lot. Even Alden Field, steeped in history, sits across the road in an athletic complex surrounding Bridgeton High School.

Recently, the complex became even more scrutinized as the last-known location of Dulce Alavez, the 5-year-old girl who vanished from the park in 2019.

Since then, extra security cameras have been added — even at the museum. The disappearance has been a worrisome mystery, but the organizers of the museum carry on.

Bass fisherman Mike Iaconelli, from Pittsgrove, became the 40th athlete inducted to the Hall of Fame in January. Former Phillies pitcher Ricky Bottalico was next in March. There’s also a display for the late hockey player Johnny Gaudreau, who grew up in Carneys Point .

During a recent visit, Bottalico estimated Mays' Gold Glove might be worth $300,000. Valella does not like to advertise that.

Then, he breaks off into a "did you know..."

Apparently, he says, Joe Louis, the world champion boxer, played in a charity softball game in town... and like most famous athletes traveling through Bridgeton, had a run-in with the police. This time, Louis’ car was flagged for speeding... in 1938.

To prove it, the museum has the autographed ticket from the Bridgeton police.

Then, there’s the story of Bernice Gera, the first female to umpire a professional baseball game in the New York-Penn League in 1972. Before that, Gera routinely called games at the Bridgeton Invitational. It was, in fact, one of her favorite places to be so her ashes were sprinkled at Alden Field and her family donated one of her uniforms to the museum. Parts of that uniform are on loan to Cooperstown.

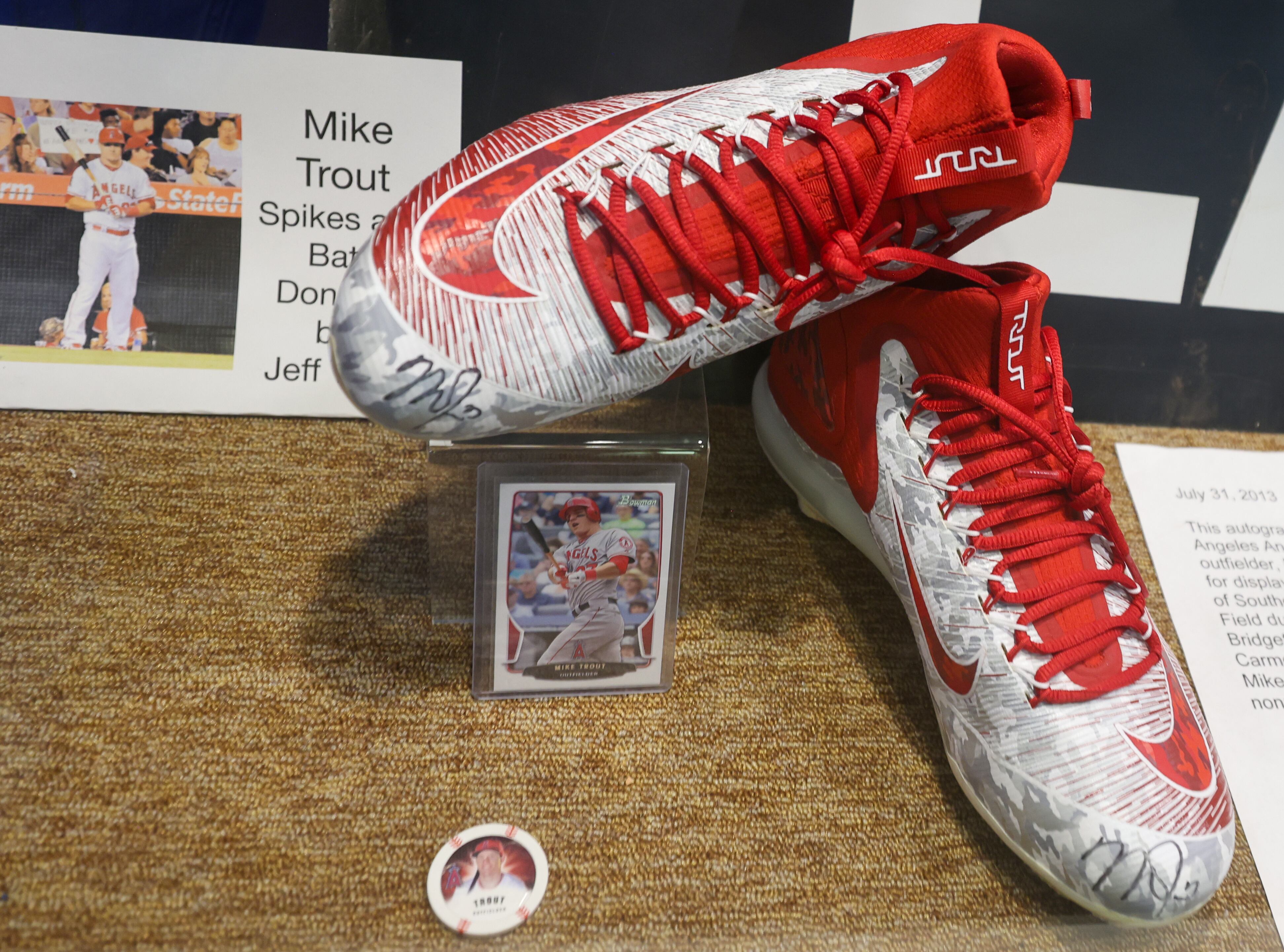

Millville's Mike Trout — headed for Cooperstown one day — already has his display at his local Hall of Fame. Valella used his connections at Citizens Bank Park to acquire a base that Trout slid into when he played at the stadium during his rookie year. He also has signed cleats donated by Trout’s father and a slew of other stuff, like a fishing hat.

Once inside, you can get lost in thousands of curious items from yesteryear — that is, if you don’t get lost finding the place.

Thank you for relying on us to provide the journalism you can trust. Please consider supporting us with a subscription.

Patrick Lanni may be reached at planni@njadvancemedia.com .

©2025 Advance Local Media LLC. Visit sastra News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

0 Komentar