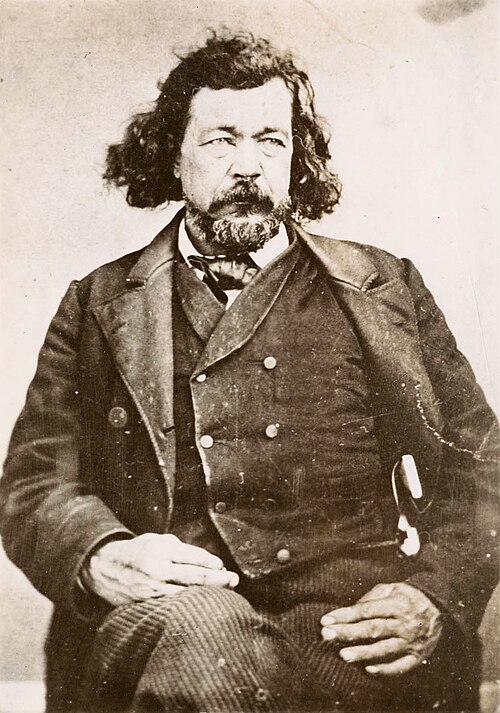

Love Creek in Ben Lomond was named after Capt. Harry Love. He was nicknamed the “Black Knight of the Zayante,” an Arthurian reference to a champion with dark powers. Love had impressive credentials, but his larger-than-life personality squeezed into a bear-like body, resembled a pirate king. He was regarded as a hero in his day, but only when his name was coupled with that of his nemesis Joaquin Murietta. The historian Herbert Howe Bancroft summed up Love as a law-abiding desperado.

Harry Love was born in Vermont in 1818. As a 10-year-old, he became a sailor in 1828 and was shipwrecked. Then in 1831, the 13-year-old served with Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War, possibly as a waterboy. Love went to Texas with his brother, where 18-year-old Love joined the Texas Rangers in 1836, and knew Sam Houston and Davy Crockett. Crockett died with Love’s brother at the Alamo on Feb. 23, 1836. Texas became disputed territory, precipitating the Mexican-American War starting April 25, 1846. The Texas Rangers were mustered into federal service, and 28-year-old Love was made captain of the Scouts under Zachary Taylor. Love often made solo Express Rides across deserts and mountains to deliver messages to distant outposts. Victory came on Feb. 2, 1848, after which Love helped explore the Rio Grande in 1850. Later that year, Love went to California for the Gold Rush. He was not successful, and instead became deputy sheriff of Santa Barbara and a bounty hunter.

The Ruddle family offered a substantial reward to catch the three men who killed their unarmed son Allen, while he was driving his wagon to Stockton. Partnering with someone, Love tracked the three killers to Pacheco Pass, then followed two of them to Buenaventura. Finally, in June 1852, one man was captured, named Pedro Gonzalez. He was part of a horse-stealing operation, driving wild or stolen horses to Sonora, Mexico, for resale. However, on the way to Los Angeles, they stopped for water, and Love killed Gonzalez when he attempted to escape.

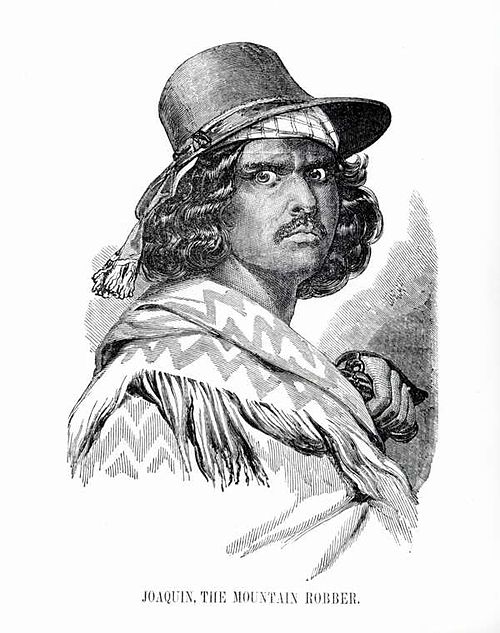

In January 1853, a crime wave hit the gold country. Chinese miners found themselves the victims of a trio of Mexicans robbing them of gold, while hanging or slitting the throats of those who resisted. So many articles recounted atrocities against gold miners, mostly Chinese, Americans, Chileans, and Mexicans. And the name most frequently mentioned was “Joaquin.” Love became intrigued, for the killer he had apprehended, Pedro Gonzalez, happened to be a relative of Joaquin Carrillo.

After a month’s newspaper coverage of constant gold country murders/robberies, Gov. John Bigler was authorized by the California Legislature on Feb. 12, 1853, to offer a reward of $1,000 for the apprehension of Joaquín Carrillo, a 5-foot 10-inch Mexican with black hair and eyes, speaking perfect English. Jose Maria Covarrubias, chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, objected to a catch-or-kill incentive for someone holding a common Spanish name, since his own brother-in-law was a circuit court judge in Santa Barbara named Joaquin Carrillo. He was ignored.

In the meantime, questions as to how Joaquin could strike here one day and 200 miles away the next became clear as they learned there were five Joaquins, each the head of a horse rustling gang, in an alliance. Three murderous months later, the California Senate and Assembly felt it was time for drastic action. Since they didn’t have a California National Guard at the time, a bill was drafted to allow formation of a California Rangers unit, to be organized by former Texas Ranger Capt. Harry Love with no more than 20 rangers. They would be empowered for three months only, to track down the five Joaquins, whose last names were identified as Carrillo, Valenzuela, Ocomorenia, Botellier, and Murrieta. It was estimated the Joaquins had stolen about $80,000 in gold.

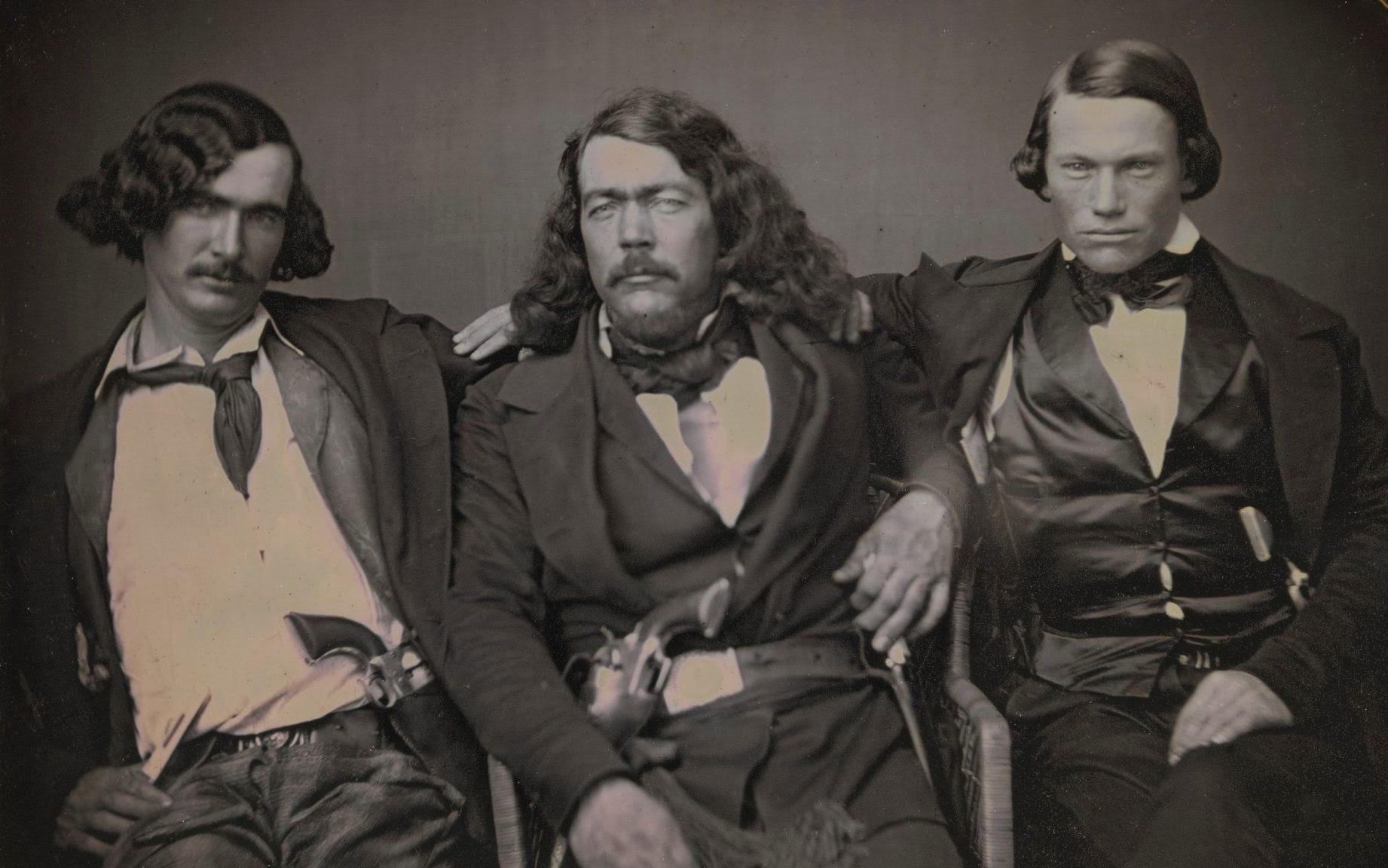

Love recruited his men at Quartzburg near Hornitos, in Mariposa County, and outfitted them with U.S. Army-issued weapons. Wm. J. Howard provided the men with quality horses from his Hornitos ranch, trained by his brother Tom, both becoming rangers. Howard had a large mule train, once operated by Joaquin Juan Murrieta and his brother Martin Murrieta. Ranger Wm. Byrnes also had once known Joaquin Murrieta. The Howards and Ranger John Nuttall later became filibusters, seeking to make Nicaragua a slave state.

Bloodsworth was called "Bloodthirsty Charlie," and Jim Norton was nicknamed "the Terrible Sailor." Ranger Wm. T. Henderson abstained from liquor and tobacco, and once caught and hanged a bad man alone. Ranger Wm. Campbell came west in 1846 with the Boggs Party, with his son founding the town of Campbell. Doc Hollister was a humorous San Jose man. And George W. Evans was described as "a noted gunfighter and killer of bad men," who later died in Santa Cruz.

Manhunt

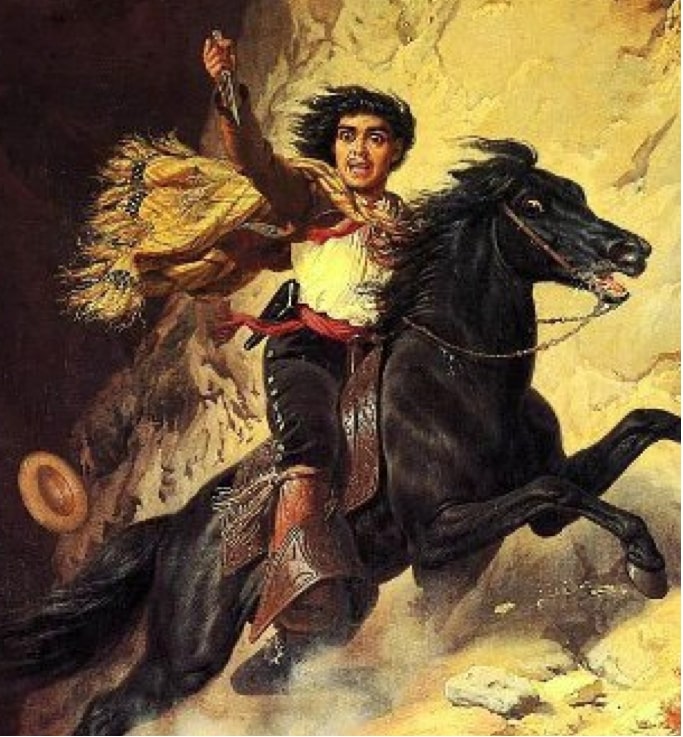

The rangers came up short seeking through the gold country, then Love arrested Joaquin Murrieta’s brother-in-law, Jesus Feliz on July 12, 1853. Love promised to free Feliz if he led them to the secret horse rustling rendezvous. Feliz said he would, but it was too late, for by now the gangs had headed for San Diego. The rangers departed Tres Pinos, and on July 20, 1853, at Arroyo de Cantua, Feliz peeked into the canyon and was surprised to see nearly 100 men and 300 horses still being branded. This was all five gangs who hadn’t left yet.

Outnumbered and already spotted by lookouts, Love boldly presented his men as field officers, selecting some horses that were obviously stolen to retrieve, while also counting the 83 men, and three women. The three rangers acquainted with Joaquin Murrieta said he wasn’t present.

Meanwhile, Joaquin Murrieta was part of a group of four men and three women. He went to Tejon Rancho, and harassed the Indigenous owners, the Tejon Chumash, humiliating them, scaring off their horses, and eating all their food. The Murrieta party then left for a good sleep, encamped at Tejon Creek. Then in the dark, the Tejons overpowered the Murrieta gang, tied them up, stole all their riches, their horses, and even their clothes, leaving them naked in a desert of prickly cactus, thorn bushes, and puncture weeds. It was the revenge of the nice guys! Many of the treasures from this revenge were reportedly passed down in Tejon families.

Near Panoche Pass, the rangers encountered a group of Mexicans gathered around a campfire with their horses a distance off. The rangers inquired as to their leader, and a haughty man said he was the leader, and they should address all questions to him. Suddenly gunfire broke out; the "leader" was shot by both Ranger Henderson and Ranger John A. White. Four bandits were killed in the melee, two were captured, and the rest got away. The captives were Jose Maria Ochovo and Antonio Lopez. The rangers identified the leader as Joaquin Carrillo, the man identified on the governor’s reward. So Ranger Jim Norton hacked off Carrillo’s head with a bowie knife, as well as the head of Manuel Garcia, known as “Three Finger Jack,” who liked to slit the throats of Chinese miners. But Garcia had been shot in the face and was hard to identify, so they cut off his three-finger hand. The rangers had brought cans of alcohol to preserve their trophies, but the alcohol had leaked out, so Ranger John Sylvester carried the trophies to Fort Miller (now Fresno County) to get alcohol in which to preserve them. Garcia’s head was buried at the fort.

Reward

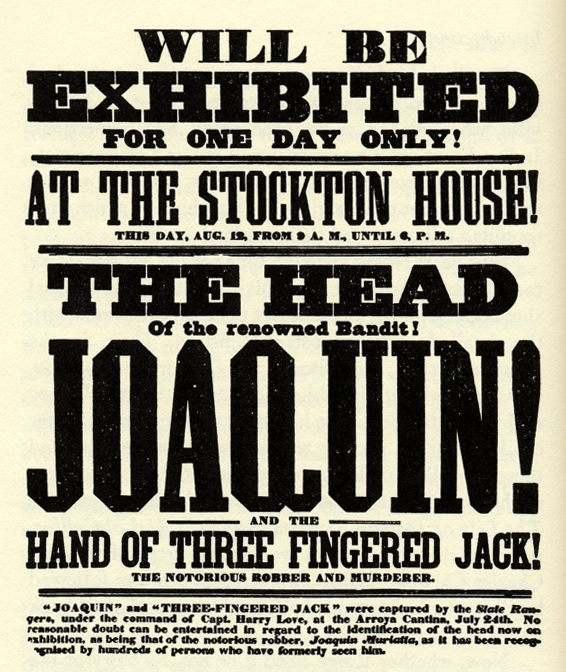

When three months were up, the governor paid 90-days wages for the captain and his rangers, plus the $1,000 reward, and in 1854 the state Legislature added a $5,000 bonus. Harry toured with the head and hand in mining camps, charging $1 for an eager public to see that the terror was ended and the killers were dead. He eventually sold the head and hand to Rangers Henderson and Lafayette Black, who exhibited them in San Francisco and various places as evidence Love got the right men. But a letter was printed in a California newspaper that said (paraphrased), "I saw the head, and must admit, it’s not my head at all!" – Joaquin Murrieta. This was part of a trend to cast doubt that these were the actual killers.

In 1854, John Rollin Ridge wrote a fanciful story called "The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta," turning a minor killer into the main character, merging the five Joaquins into one supervillain, with a sympathetic backstory about an anti-Mexican mob beating Murrieta while his wife is raped in front of him. It justified Murrieta’s bloodlust by only killing those who deserved it. Love had become a folk hero, but of someone else’s story.

Love took the hand of Mary Bennett in marriage and bought back the mill her sons built in 1848 but had lost for back taxes in 1851. Love had fame, property, money and matrimony. But Harry and Mary were both unyielding personalities accustomed to getting their way. It was a marriage of violence, rages and beatings, frequent break-ups and make-ups, until Mary moved to her own home in Santa Clara, hoping to finalize a divorce in 1866 but failed. Meanwhile, the mill suffered from an 1862 flood, then an 1867 fire, and his home burned in 1868, leaving Love homeless, in debt and defensive of his legacy. Mary hired a bodyguard to keep him away from her, so he moved to his wife’s old ranch, living in a house she’d built for him.

Captain Love reasoned that he and Mary had once been happy, and concluded that the only thing keeping them apart was her bodyguard, Christian Iverson, who was acting like her husband. On June 29, 1868, Capt. Love went to his wife’s house in Santa Clara, but she wasn’t there, so he stationed himself inside the gate, like an old-fashioned criminal stakeout. When Mary and Christian Iverson approached, Love fired at the carriage, a near-miss that cut Iverson’s hand. Mary screamed, frightening the horse, which Iverson had to calm while trying to get his gun out of his holster. Iverson got out of the carriage and went up to the gate. They both fired at the same time. Iverson missed, but Love hit him in the right arm. Iverson then took the gun in his left hand and shot Love at close range in his right arm. Screaming in pain, Love tried to get away, but Iverson clubbed Love in the head several times.

The doctors found Love delirious, his right arm bone shattered, which would have to be amputated. They administered chloroform, but it had no effect on the old bear, so they gave a bit more. The operation was a success, but the patient died. Of all the things Capt. Love could do, his greatest failure… was love.

Further reading

"Bad Company," Joseph Henry Jackson, 1949. "Joaquin Murrieta and his Horse Gangs," Frank F. Latta, 1980.

0 Komentar